| Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir |

|

|

|

|

by Adalsteinn Ingólfsson

In the last ten years or so, Icelandic graphic art has come of age. For over half a century the other arts, chiefly painting and sculpture, dominated the Icelandic art scene, but through foreign exhibitions of high-quality graphic art and the emergence of a new breed of graphic artists trained abroad an atmosphere of intense activity has been created and the public has responded eagerly.

One indication of the new status of Icelandic graphic arts is the number of awards our artists are now collecting at international graphics exhibitions all over the world - such as in Yugoslavia, France, South-America and Poland. One of the most active participants in these international venues, and a winner of important prizes for her graphics, is Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir. Her progress is all the more remarkable when we consider that she is an active mother of five and, moreover, only started working seriously in graphics art at the end of the sixties. She is also unusually aware of social issues and is unafraid of commenting on them in her graphics, without compromising her feeling for the formal necessities of a work of art - i.e. by realizing that a picture has to be effective as a composition before it can function as a message.

Bursting with Energy

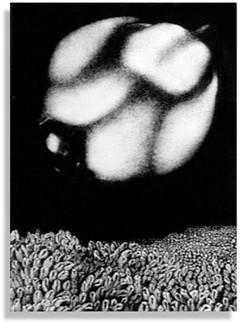

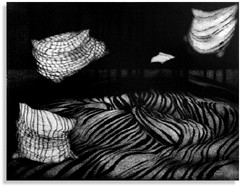

Like so many others before her, Ragnheidur creates a set of personal symbols, which unmistakably refer to immediate social issues, like the condition of women in modern society or the state’s interference with the natural course of the arts, but at the same time these symbols are potent enough to suggest a wider significance - the role of women through the ages, the wold over, and the attempts of every state from time immermorial to use the arts for its own ends. Behind all of Ragnheidur’s graphics, there is a constant preoccupation with the freedom of the individual, especially the creative artist. In her early work, this is expressed in a near-abstract manner by the combination of hard, geometric shapes and softer forms which often suggest human limbs, and invariably these ‘living’ shapes seem to be contained in some way by the rigid geometry packed, sealed, delivered : unfree. This preoccupation becomes more noticeable the further we come into the seventies, and so do Ragnheidur’s technical advances. The soft ‘living’ forms take on more recognizable shapes : pillows are tied to steel bars, flowers are juxtaposed with brutal, block-like structures that suggest modern prisons, and then the flower-shapes are again abstracted to form huge, almost palpitating symbols, bursting with energy and eroticism, looming over an earth crawling with lesser life. The One against the Masses.

The Chair Symbol

But sometimes these living forms take on a more sinister aspect in Ragnheidur’s works, frequently when combined with her symbols of official power, the chairs or thrones. And immediately we notice the different treatment of the soft forms. They are no longer open and alive, but closed up, shrunken or bloated - perched upon their thrones like bad-tempered toads, and often Ragnheidur places them within recognizable surroundings. In a picture called ‘Glundur’ (Mish-mash) one of these unattractive shapes sits in a high-backed chair, wedged between the ponderous ceiling of Reykjavik’s Municipal Gallery and block of houses below, suggesting that both are dominated by a similar kind of crude power; the image is powerful enough to take us beyond local politics and into a larger political arena.

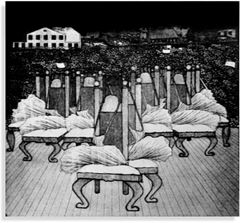

Sometimes Ragnheidur will use the chair symbol on its own, as a powerstructure, ironically placing a huge drawing pin upon it, as if to deflate the pomposity that often goes with high office, all over the world. but there are also two sides to the chair-symbol, as in Ragnheidur’s treatment of the soft shapes. In a picture called ‘24th of October’, which is a celebration of the Icelandic women’s general strike on that day in 1975, she shows a row of fancy chairs upon a stage in the foreground, with crowds of women at the back. Each one of the chairs has an apron tied to it, which is being blown off, possibly by the new-found power of the women’s movement. Presumably this means that women are coming to the fore, rejecting their traditional roles and occupying the seats of power to redress the balance.

The Viewer is Puzzled

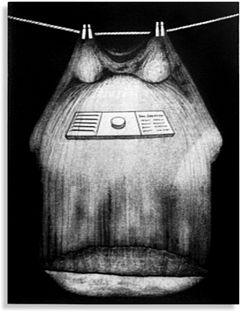

But occasionally Ragnheidur’s use of symbols is more ambiguous. What are we to make of her memorable image of the pregnant dress on a chair? Certainly the artist is referring to the stereotype of woman as a dressed-up doll whose function is primarily child-bearing. Her personality is obliterated. But is she tied to the chair - the male pover-symbol - or does the chair signify that she is verily the pover-to-be? The viewer is puzzled, but surely stimulated into thought. It is this quality that makes Ragnheidur’s graphics such exciting propositions - her ability to create symbols which are formally powerful and, at the same time, intellectually appealing.

Published in Iceland Review 1978.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|