| Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir |

|

|

|

|

Pictorial Art as a Weapon

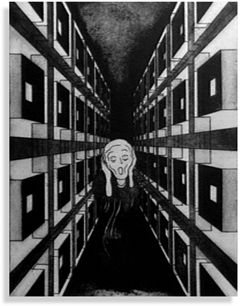

The exploitation of pictorial art as a political weapon, to inform, expose and to connect with other forms of social criticism has become more and more common in the last few years. The works exhibited by Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir at present in the Nordic House count as such social dissidence, touching on a wide variety of subjects. Her works deal with, amongst other things, alienation, male power and female powerlessness, pollution, damage of the environment and lack of social responsibility.

Ragnheidur has adopted the method of creating picture series which have a unifying main theme although this does not at all prevent viewing each work as an independent entity. It cannot be denied, however, that its meaning becomes more clearly defined by viewing it in context.

From 1969

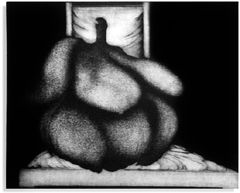

The earliest works at the exhibition date from 1969, these works probably being her earliest graphic works. These pictures are characterized by a sensitive play with lines in some undefined space, where light transforms the formal mass in numerous ways. Soon, however, the picture space becomes more stable and the forms more organic, all of this being fitted into a strictly delineated frame. In the series, ‘The human cage’ from 1973, psychological content is created by the struggle of organic forms within a clearly defined space, either being squeezed or allowed some elbowroom. This type of content is further underlined in the series ‘Stop the world!’ from 1973, where the formal structure is all more to the point and each form is given a stronger psychologcal content, which suggests alienation, human insecurity and similar things which also crop up in her later work.

‘2001-2006’

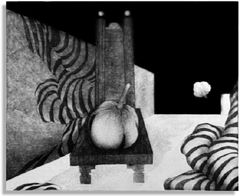

The series ‘2001-2006’ from 1974 in many ways opens a new period in her career. In these works the formal structure has undergone change in several ways, and she occupies herself to a greater extent with whole surfaces and more clearly separated forms, which have a more precise meaning, both between themselves and each by itself. Here the two symbols that she makes great use of in later series first make their appearance. These symbols are, on the one hand, the chair, which she endows with many kinds of meaning, whether as a symbol of isolation, storage or weakness, and, on the other hand, a convex organic form which might be labelled the ‘tulip-form’, which above everything becomes her symbol of Nature and living environment.

In this series, which deals with Nature and our intercourse with it, she confronts opposite picture symbols with each other, typicalli on a surface divided into two parts. The ‘tulip-symbol’ becomes a kind of agent in these works, where it is, amongst other things, put on a chair, a symbol of the storage and isolation of Nature, something that is an object of observation instead of embracing and being part of the human environment.

‘Leaders of the People - 2010’

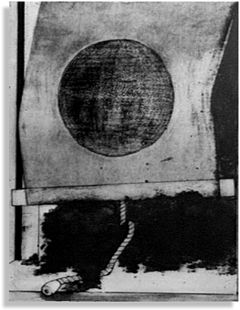

If the gradual disappearance of Nature is the dismal theme of the series ‘2001-2006’, then the vision offered of the future in the series ‘Leaders of the People - 2010’ is hardly more optimistic. This series deals with the pullution of the environment, lack of initiative and of social responsibility. The subject here is the main motto of our consumer society ‘to use and throw away’, the filth of consumption and our lack of responsibility in rappling with the consequences.

In this series she works with simple pictorial symbols such as window forms with a roller-blind which covers the whole surface. The window becomes the symbol of isolation, the fear of facing the facts about our tendency to retreat into our own private worlds and our failure to assume social responsibility. The series becomes a kind of doomsday description; in the last picture, ‘2010’, as nothing can be done now, the window gives under pressure, the sun is hidden behind a cloud and the human race is drowned in the garbage of its own consumption. But the series is not just a foreboding or a judgement day picture of the irresponsibility of consumer society, but also exposes the reason behind the form of society depicted in ‘Leaders of the People’. The picture of a group of men with white collars and carefully hidden eyes in their irresponsibility and who are formally reprensented as grown together into a community of mutual insurance, a community based on the principle of closing one’s eyes to the facts. There is increase in economic growth, in production and consumption, but still one has forgotten to count in human environment and well-being in the economic growth calculations. Or could this picture perhaps be interpreted as a symbol of the impersonal power of the economic system which has quick profits as its guiding light and evades social responsibility.

‘Excess weight - 2011’

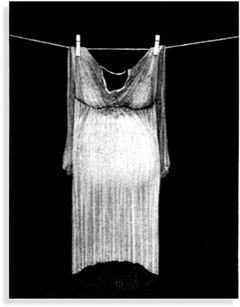

In this exhibition, Ragnheidur does not confine her opinions to her views on our interrelationship with Nature. The social status of the fellow members of her sex is the subject of the picture series ‘Excess weight’, which is an exaggerated and stylized image of the female as a fertility symbol, a graphic ‘Venus of Willendorf’ dating from 1975. But the female is not just a fertility goddess, she also has something to fight for and a picture is drawn exhibiting a view of the Women’s Day meeting at Lækjartorg where thousands of women showed solidarity in their battle against sex discrimination. But the huge crowd of people is not portrayed by the artist as a collection of living individuals; rather, it is transformed into a expanse of moss - a memory overgrown with moss. She also fixes her attention on the multitude, extracts its denominator, which becomes a symbol of the social status of women. At the same time various symbols make their reappearance, such as the chair symbol, now with an apron, a reference to the social isolation of women and of their storage place.

‘Glundur 75’ I - ‘Glundur 75’ IV

It is not only ‘the big issues’ which stimulate Ragnheidur’s artistic creativity. The so-called ‘Kjarvalsstadir affair’ of some years ago is the subject of the series ‘Glundur 75’. This affair turned on a quarrel between the minicipal authorities and the Association of Artists about the aristic evaluation of exhibitors at Kjarvalsstadir. The baroque lighting of Kjarvalsstadir makes its presence felt in each picture and dispels any doubt as to the subject. Here use is made of several symbols which have already occurred in other series, for instance, the chair symbol which symbolizes authority and there are also other symbols for the numerous parties involved in the conflict. Perhaps this series is the weakest one as regards pictorial value as the pictures become, first and foremost, descrptions of a definite course of events in symbolic laguage whereas a convincing pictorial unity is lacking. This conglomeration of pictorial symbols is always tied to the particular without ever achieving a more universal content.

Admirable Workmanship

Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir’s pictures relate to important social issues where the message never overburdens the form. Her treatment of form, when she is at her best, is precise and chiseled, whether her medium is etching, aquatint or drypoint, and her graphic workmanship is admirable. Considered as a whole, Ragnheidur’s treatment of social problems is primarily descriptive and never a commentary upon how these problems might be solved or on social change. Here perhaps we have also reached the limits of the power of art, since overthrowing the present social structure requires something more than artistic efforts. It requires, in addition and primarily, active political engagement. The artistic picture alone and by itself can never bring about a social revolution.

Published in Thjódviljinn 17 October 1976.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|