| Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir |

|

|

|

|

by Adalsteinn Ingólfsson

‘From a dignified relationship with the land, it is possible to imagine an extension of dignified relationships throughout one’s life. Each relationship is formed of the same integrity, which initially makes the mind say: the things in the land fit together perfectly, even though they are always changing.

I wish the order of my life to be arranged in the same way I find the light, the slight movement of the wind, the voice of a bird, the heading of a seed pod I see before me’. (Barry Lopez-Arctic Dreams, p. XXIII).

For centuries Icelanders have been trying to forge a ‘dignified relationship with the land’, to use Barry Lopez’s words. They tried to claim the Icelandic landscape for themselves by naming everything in sight, down to the most insignificant brook or hillock. In time the land provided them with a living, became their measure of time, a depository of their memories and a midwife to their myths and folktales. The Icelandic landscape, beautiful and bountiful as it was, also tried its best to destroy its inhabitants. The history of Iceland is littered with freakish natural catastrophes, eartquakes, avalanches, sub-glacial debacles and volcanic eruptions with its attendant floods and suffocating dust. Throughout it all, Icelanders continued to look to this eerie and treacherous landscape for material and spiritual comfort.

Iceland’s first professional artists, landscape painters all, exhibit no sense of the underlying menace of their chosen subjectmatter, perhaps with good reason. Educated in Denmark and fiercely nationalistic they were nurtured on the comfortably European iea of ‘beauty’. They believed that the national pride of Icelanders could be stimulated through the extolling of ‘the natural beauty’ of the Icelandic landscape and proceeded to do so, often very succesfully. Icelanders themselves had never connected the landscape around them with the idea of beauty. To them ‘beauty’ resided in the man-made and well-made, a clever peace of verse or a carved bowl. Not until the mature work of painter Jóhannes Kjarval (1885-1972), executed in the late 1920s and early 1930s, do we get a sense of the ‘totality’ of the Icelandic landscape. In his hands the Icelandic landscape ceases to be conventionally picturesque. It is at the same time nurturing and destructive, mischievously gay and brooding, intensely lyrical and dramatic. Kjarval´s best landscapes are teeming with a sense of past events as well as the present moment. It is as if the artist wanted to capture not only the land in its concrete aspect, but also the weathers it has endured, the tales it has engendered and the presence of the generations of Icelanders who passes through it.

Somewhat surprisingly, Ragnheidur Jónsdóttr has become one of very few Icelandic artists to ally herself with Kjarval’s holistic interpretation of the Icelandic environment. Moreover she has extended it to include the larger view, both of nature and humankind. I say surprisingly, for a few years ago one would not have expected a printmaker, even one as distinguished as Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir, to aspire the monumental orientated compositions of the kind that she has been creating of late.

In retrospect, the seeds of these compositions were clearly shown in the series of prints that Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir was working on formost of the 1980s. In the 1970s, the artist had tried to extract deep meaning from everyday objects, often with great success. Some of her images such as the ‘pregnant dress’, ‘pillows’, with their overtones of suffocation, or the ‘fancy-cake head’, have achieved an iconic status, especially within the Icelandic woman’s movement.

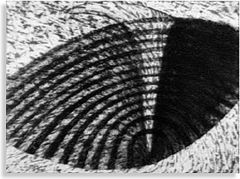

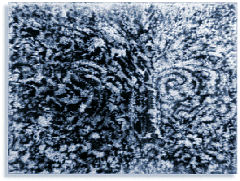

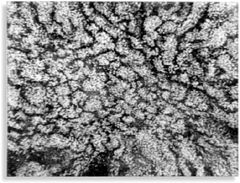

In the 1980s, Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir turnes her attention to the human presence/interference in nature, especially to signs and symbols that people have seemingly been using to mark their desire for a openess with the mystery of creation, from ancient spiritual drawings and fertility signs to 20the century cairns. In her present graphite compositions, Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir goes beyond those signs and symbols, to fling herself headlong into the heart of creation. This has entailed a radical reevaluation, not only of her artistic philosopy but also of her working methods. In printmaking, the artist huddles over a pictorial world proscribed by the size of the printing plate and the sheet of paper. Composing on huge sheets of paper mounted on the wall stretches the artist both mentally and physically. He takes more chances, becomes a part, sometimes a victim of the creative process that he unleashes. Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir relishes this new challenge. Living next to a craggy lava field garnished with sponge-like moss, with a view both of a extinct volcano, a boundless sea and even more boundless sky, she is uniquely placed to ponder the nature of the drama before her. Her work is never a record of a particular place, as Kjarval’s paintings always are, but a distillation of its spirit. We are presented with the softness of moss, the sharpness of lava, but also the movement of grass, the passing of clouds and the falling of rain. Ragnheidur Jónsdottir’s vision takes us beyond the ‘fact’ of nature, to the hidden processes beyond it, the forces slowly chipping away at its foundations, eroding it, changing it imperceptibly.

Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir’s ‘places’ also evoke - and question - the human presence. We catch a glimpse of a faint footmark here, the pressure of a hand there, perhaps also the remnants of a object brought and halfburied by nature.

Recently her work has also hinted at a more ominous human presence in nature. Her motifs become hazy, indistinct, like one of her ‘places’ seen through smog or black clouds from bombed-out oil wells, or they seem to have turned to cinder by the onslaught of fire storms. Once or twice the viewer even feels the presence of the dreaded mushroom cloud.

At this point in time, will we ever be able to have that ‘dignified relationship with the land’ mentioned at the outset? This is perhaps the central question posed by Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir’s present and impressive work.

Published in DV 21 February 1994

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|