By Jón Proppé

These works are a curious combination of restrained formalism and uncontrollable force, universalised abstraction and site-specific, earth-bound realism. They reveal a creative process that is neither fully contained, nor again entirely arbitrary. The result is correspondingly complex: on the one hand the exhibition has an air of sophistication and calm, and on the other hand one senses danger and anarchy despite the carefully thought-out nature of the works.

Gudjón Bjarnason has exhibited sculptures before, made with the same material he now uses, and concentrating, similarly, on basic forms. But the formalism of the older sculptures is now augmented by several new elements, most obviously in that the sculptures have now been literally exploded, blown apart with dynamite, in some cases blown away altogether, leaving only fragments or an absence. The site of these explosions is important to an understanding of the works and photographs of the site form a part of the exhibition. Gudjón picked an abandoned open-cast mine in a lava field in Iceland - a place where men and machines have gauged a gigantic rift in the landscape, leaving a place that seems to belong neither to man nor to nature, a post-apocalyptic desert where no life can take root. This is where the sculptures are created, using force that can only be partly controlled, with results that can only be partly predicted. Parts of the sculptures - in some cases whole pieces - are inevitably lost in the process, scattered and left behind, connecting the sculptures to the place of their creation, no matter where they might be exhibited; they are specific to the site where they were made and appear transplanted in the gallery, taken out of context, their jagged edges testifying to the force that was unleashed in their creation, like shrapnel strewn across a battlefield. This is art seen as war, a violent struggle with no guarantee of victory.

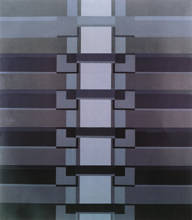

The juxtaposition of strict formalism and elemental chaos is repeated in the paintings. Gudjón exhibits paintings that are the result of careful geometric calculation - entirely abstract reworkings of the possibilities inherent in the most basic forms, crosses and simple angels, perhaps most reminiscent of the works that Ad Reinhardt produced in the 1950s, though by no means imitating them. These paintings appear side by side with other paintings that, much like the sculptures, are chaotic and organic, the result of some process that does not seem to be entirely under control. The tension between the two is what informs the exhibition, a tension that implies a dangerous duality, an edge that the artist walks along, attempting to balance elements that cannot be blended but only presented as contradictory, yet complementary options.

Control and chaos are the two extremes that define the creative process, leading the artist along his unique path, ‘just as independent and just as incomprehensible as the path of the lunatic for whom all step aside in shame,’ as El Lissitzky described it. While chance can never be the primary force in art it must always be present, at least in the sense that the artist must be willing to take chances, to relinguish control and to accept the result of forces that operate outside himself. Gudjón Bjarnason’s works illustrate this perfectly and he has become expert at handling the energy of this creative process, directing it without ever containing it fully. The process is judged by its result, but at the same time the works that are its result are testimony to their creation, embodying the history of their own making and sometimes, as in the case of Gudjón Bjarnason’s sculptures, the places where they came into being.

The works themselves are structured to reflect the gradations between control and the uncontrollable. Repeated forms are exposed to varying degrees of deformation and thus exhibit all the better then tension that is inherent in the artist’s working method. The gradations in colour that can be seen in the paintings and in the cast-metal body parts that accompany them again reflect process, movement, and underline the unstable nature of the artistic project, streched out between two extremes of light and darkness, control and chaos, ‘as incomprehensible as the path of the lunatic’, yet in essence an integral part of human existence.

The cast body parts are an interesting addition to the exhibition, a sign of human presence in a context that otherwise seems governed by inhuman forces, the logic of geometry and the chaotic power of explosions. They even hint at a humorous solution to the problem that the other works present. They assert a definite point of reference from which we can assess the abstract forces at work in art: a human scale by which we can measure these forces and understand their operation to some degree.

Just as the creative force can never be fully contained in art, so art can never be fully contained in our experience or in our writings about it. It becomes rather a point of departure, a trigger for a new and often unexpected path that the viewer or reviewer must then travel, surrendering himself to the way of the lunatic. The path we take is determined in equal parts by reason and by elemental forces that are ultimately unknowable and, like dynamite, only partially controllable. An essential part of understanding art is the realisation that, like the artist, we must be willing to relinguish control. This is always a frightening prospect and it accounts for the slightly menacing force of all good art. There is always an element of danger present, a slight hint of lunacy, even in the most meticulously crafted artwork.

It is not often that one sees the contradiction inherent in art so glearly exemplified in an exhibition. They are not resolved, of course, and could not be since they are the motive force in art. But in seeking a resolution, and especially in bringing these contradictions into sharp relief, we can further our understanding of the artistic project and perhaps to some degree of the human condition in general. Like philosophy or literature, art has the ability to engender such understanding. It is ‘the act of bringing truth into being,’ as Merleau-Ponty said, and it can do so only insofar as it is not content merely to reflect the world or to copy common ideas and preconceptions. It is only when we are willing to relinguish control and allow the world to speak for itself through our art that we can hope to create something new, a new way of seeing or a new understanding.

Jón Proppé works in Reykjavík, writing and lecturing on art and philosophy. He is a regular rewiever for the Reykjavík daily newspaper Morgunbladid and is chief editor of art.is. This text was printed in the catalogue for Gudjón Bjarnason’s exhibition in the Nordic House in Reykjavík in the summber of 1997, entitled Large Works.

text © Jón Proppé

artwork © Gudjón Bjarnason

Exploded steel, oil and varnish, approx. 33 x 33 x 700 cm

Oil on canvas, 233 x 202.5 cm

Oil on canvas, 233 x 202.5 cm

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|